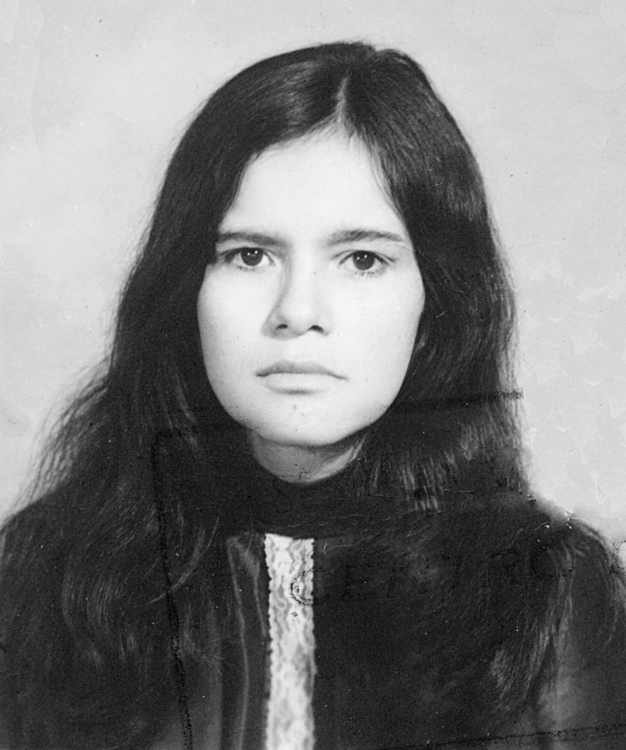

23 Jul Marina Chapman

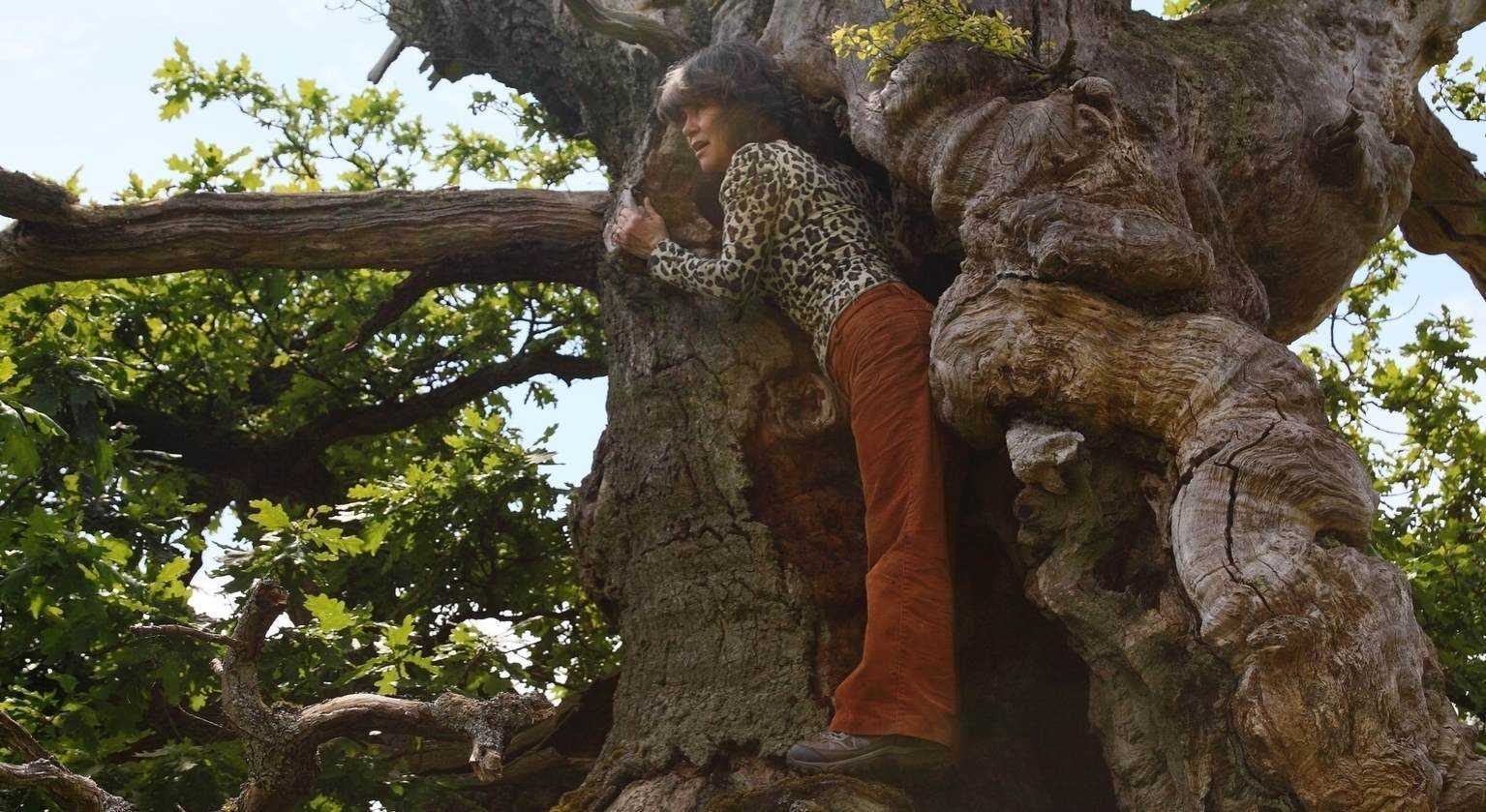

Photo by John D. Chapman | Courtesy of Marina Chapman

Marina Chapman

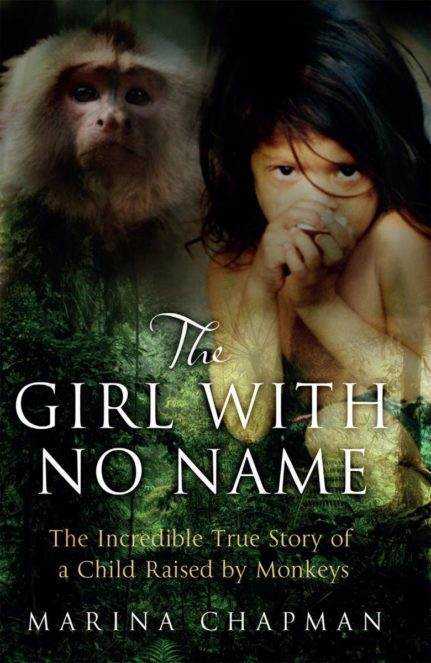

A child raised in the jungle by monkeys—that sounds like an extraordinary tale for a Hollywood movie. In 2012, the world was amazed to discover the life of Marina Chapman through her first Sunday Times bestseller memoir, The Girl with No Name, which she co-wrote with her daughter Vanessa Forero. It is the story of a child abducted at four, left for dead in the Colombian jungle, and raised by a horde of monkeys. I had the privilege of speaking with Marina Chapman for a very humbling moment of greatness. Here is her story, from darkness to light.

By Victoria Adelaide | July 23. 2018

Victoria Adelaide: Mrs. Chapman, can you briefly tell us what happened to you when you were a child?

Marina Chapman: Just a bit before my fifth birthday, I was abducted while playing with pea pods in the garden of my parents’ house in Colombia. I remember the truck. I heard children behind the truck and I heard what was happening to them. Then, for a reason I’ve never understood, I was left in the jungle. I thought my mother would come to pick me up and I waited for her—but that never happened. Perhaps it was better for me to end up in the jungle rather than in the city after all. I’ve heard kids were abused in the city. We believe about five years passed, as I could not keep track of time during the ordeal. However, scientists have estimated I must have spent five years in the jungle.

VA: How did you first connect with the monkeys?

MC: Well, I had no idea what was in the jungle until things began happening. The first animals I saw were the monkeys. They were curious—checking on me, pulling me, poking at my eyes—I wasn’t very happy about it and I remember I began crying. I remember how strong they were, just pushing me with their fingers. They felt so strong to me.

VA: At some point, you got very sick?

MC: Yes, I did. I was eating some seeds that were really tasty, with soft sticky brown flesh that I opened like I would a pea pod. I ate too much of them and got very sick. What happened next was incredible. This animal, a monkey, it was an old monkey, he came to me. At first, I thought he was going to kill me. I was terrified, but he actually saved me. He took me to the water and forced me to drink. I was scared but, looking into his eyes, I understood he meant no harm. He was there to help me. I looked at him with respect because he seemed to be in charge.

VA: Looking back, what did the monkeys teach you about life?

MC: To be safe. To be prepared for any danger. In the jungle, being as small as I was, was quite an advantage. I could hide behind bushes and prevent myself from being seen. As time went by, I also learned to recognize the sound of danger. It’s like a language; it’s a very sharp sound they make when there is danger.

VA: In your book, The Girl with No Name, you said that at some point, you did not even think of yourself as a human anymore—you thought you were a monkey.

VA: In your book, The Girl with No Name, you said that at some point, you did not even think of yourself as a human anymore—you thought you were a monkey.

MC: At some point, I did. Because you forget what you look like as there are no mirrors around. I looked at my reflection in the water but I thought I looked like them. I was confused. I was looking at them and we had the same hands. So, I was wondering, “Did I come from them?” I was a little child, I was totally confused. Then, I found a piece of mirror and I could see my face for the first time again. I realized that I was not like them and it was even more confusing because I thought they were my family. I didn’t remember my previous human family. I was a little child, growing up in the wild with them at such a young age. Subconsciously, you gradually start to feel like they’re your family. I didn’t realize it. It felt natural for me to see the monkeys as my family because I did not know any other. They were always around. I was very isolated; I just wanted some company and they were there. If it wasn’t because of those animals, I don’t think I would have survived. I would have had nothing to eat. They were good at stealing things from people. They knew when people went to sleep and they sneaked and got the food. They always carried so much, so I just had to grab and eat. I always ate very quickly. If you don’t eat quickly, they take the food away from you because they watch what you have in your hands. They’re very watchful animals and they take anything out of your hands. My husband says I eat too quickly and I grab things, but I have changed, believe me. Behavior correction therapy helped me a lot. I had to change so much and I had to learn so much. I’m still learning and I’m still having difficulties learning.

VA: You were taken out of the jungle at about age 10 and ended up in very bad houses where you were beaten, kept almost like a slave, tied to a tree etc., then you became a street kid for several years. Being a street kid must have been a very scary experience.

MC: I’ve learned a lot. I became mature by being observant. I couldn’t speak human language when I was taken from the jungle. I was about 10 then and I had forgotten human language during my upbringing in the jungle with the monkeys. Somehow, I learned with other street children. They used to teach me and made me repeat words like “arbols,” which means trees. They made me repeat words so I could learn how to say them. They taught me how to pick food and how to do things like open a door. I had no idea how to open a door. I was completely different from other children. I watched people and children, then I reproduced what they did. If it wasn’t because of that, I wouldn’t be able to do anything today.

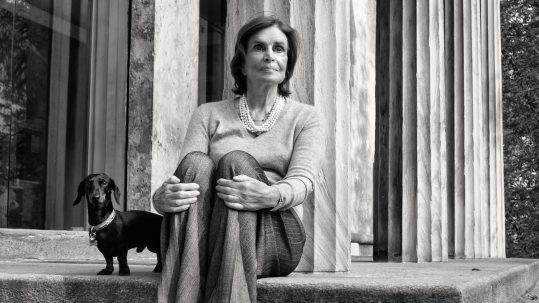

VA: Having experienced such ordeals early in life, you were finally adopted by the Forero-Eusse family, who treated you with great kindness and provided you with everything you needed. At some point, they flew you to Bradford, Yorkshire, England with other family members for a few months. Then, you met your future husband, John D. Chapman, a scientist! Can you tell us about that?

MC: Yes, I did. I was sent to England for only three months as I was set to go to America to work as a nanny for a lawyer and his wife who was a social worker. They wanted me to care for their children and they would pay for my education in exchange. That was the deal. However, in the end, I stayed in England and I met my husband. He was the first person with whom I could share the truth about my childhood without being ridiculed. We got married and now I have a family. Having a family is very precious to me because, in the animal world, it’s important. They all protect each other and that is really what I love about having a family.

VA: How did it impact your parenthood?

MC: It was difficult. I had some help. The wife of an inspector of education, who used to live nearby, helped me to be a mother, to raise my children, and tried to educate me—things like that. Sometimes, I reflect on how some people, such as those at my church, witnessed my struggles in trying to be a lady. My husband tried for many years to make me become a lady and I’ve just never been able to become one. I still have this wildness in me.

VA: What were the hardest challenges you’ve had to face when you returned to civilization?

MC: I had to wear clothes. I had to wear shoes. I was not used to wearing clothes. I hadn’t worn clothes for years but I got used to it. When I returned to civilization, I found it difficult to pick food, clothes, or anything. I could just not behave like a normal child. I had difficulty with that. I used to steal food, run to the garden, and then eat it under the bushes. I don’t do that anymore. I don’t climb trees anymore either. I’m very grateful for the help I received. It was difficult and I still find it difficult to learn many things. I’m still struggling.

Photos 3 & 7 by John D Chapman | Photos 4, 5 & 6 by Carl Bromwich | Photos courtesy of Marina Chapman.

VA: At first, what did you think about human life?

MC: I found everything complicated. I found life has always been complicated for me. I always try to do things; however, it’s often in an unsophisticated way, such as grabbing something and running or trying to open a package with my teeth—things like that. I try my best not to do it anymore. I also had to learn how to stand on my feet, as I was on all fours in the jungle.

VA: Being brought up the way you’ve been, are you scared of anything?

MC: I’ve never been scared of anything. I lived surrounded by danger. I’m used to danger.

VA: I know that originally, you didn’t want to tell your story. The initiative came from your daughter.

MC: No, I didn’t want to do it. When you grow up and start realizing things, you feel embarrassed. You want to behave better. I try to behave as normally as possible. I was bullied as a child, and I didn’t want my daughters or my grandchildren to be bullied at school. I was keeping quiet to protect my family. One day, a policeman laughed loudly in front of me because I talked about the monkeys. After that experience, I never wanted to say anything to anybody. I didn’t want people to be laughing at us or mocking us.

VA: After the book was published, you had to face the disbelief of some people. So, you decided to go back to where everything started, in Colombia, to see places where all of it happened, and you underwent extreme medical tests that proved you were right. What was it like for you to experience all of that to show the world that your story is real?

MC: I did it because the book was written. People needed to know that my story was true. I was absolutely fine with having to undergo those medical tests. I didn’t mind. It was a good thing to do it, as they showed in the end that I was telling the truth. As a result, I’m not afraid anymore about my grandchildren getting bullied at school or anything. I am fine with that now. People have been great; they understand now. It’s incredible they’re not bullying me anymore. I don’t behave the way I used to. I have been in trouble in the past for climbing walls and chimneys—I don’t do that anymore. (laughs)

VA: Do you think animals can sometimes show more humanity and compassion than we do?

MC: Indeed. They do have understanding. They have instincts and they feel. That instinct, if you keep it with you, you’ll be safe in life.

VA: Are you happy now?

MC: Yes, I am. I have a family. I never thought I was going to have a family. The greatest thing that happened to me is my daughters. They are the most precious things in my life and I love them. I realize there is a God. God is gracious. My life was disciplined and corrected and I’m grateful for that. People were good to me in the end.